I initially welded a large steel armature that would support the weight of the clay and produced a ten-foot tall copy of an existing three-foot model of the sculpture by simply modelling mud over the armature. I used a live model just to improve the modelling of details, such as the form and gesture of the hands.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

Once the plaster mold was completed, we began to pull apart the individual sections. Later we melted microcristalline wax and painted it on the inner surface of the mold sections building up several coats until reaching 1/4" thickness.

At this point we had produced a wax replica of the original clay in twenty-two sections. We were ready to begin the "lost wax process". This technique was invented independently by many peoples throughout the world:The Chinese, Mesopotamians and Archaic Greeks among them. Sculptors formed their images or idols in wax. This wax sculpture or "pattern" was then "invested" or coated with a creamy material composed of gypsum (plaster), clay and silica (sand) that hardened to form a mold. The mold was then heated in a kiln (burnout) the pattern melted away and was "lost". Metal was then poured into the cavity left by the "lost wax", thus duplicating the original wax pattern in metal. With a few variations in these investment materials and other technical advances, this casting process has remained virtually the same since its inception 5,000 years ago. Today is known also as the standard investment method.

Next we produced a wax replica of the original clay in twenty-two sections. We were ready to begin the "lost wax process". This technique was invented independently by many peoples throughout the world:The Chinese, Mesopotamians and Archaic Greeks among them. Sculptors formed their images or idols in wax. This wax sculpture or "pattern" was then "invested" or coated with a creamy material composed of gypsum (plaster), clay and silica (sand) that hardened to form a mold. The mold was then heated in a kiln (burnout) the pattern melted away and was "lost". Metal was then poured into the cavity left by the "lost wax", thus duplicating the original wax pattern in metal. With a few variations in these investment materials and other technical advances, this casting process has remained virtually the same since its inception 5,000 years ago. Today is known also as the standard investment method.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

Next we produced a wax replica of the original clay in twenty-two sections. We were ready to begin the "lost wax process". This technique was invented independently by many peoples throughout the world:The Chinese, Mesopotamians and Archaic Greeks among them. Sculptors formed their images or idols in wax. This wax sculpture or "pattern" was then "invested" or coated with a creamy material composed of gypsum (plaster), clay and silica (sand) that hardened to form a mold. The mold was then heated in a kiln (burnout) the pattern melted away and was "lost". Metal was then poured into the cavity left by the "lost wax", thus duplicating the original wax pattern in metal. With a few variations in these investment materials and other technical advances, this casting process has remained virtually the same since its inception 5,000 years ago. Today is known also as the standard investment method.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The twenty-two sections of "Gaia" were individually coated with a new refractory slurry, called "Ceramic Shell", which is a modern variation of the standard investment method. Ceramic shell is a true "lost wax" method but instead of the former plaster clay, sand investment, a refractory slurry composed of colloidal fused silica and fused silica stucco grain is used to make the mold.

The wax sections were first dipped in the colloidal slurry, then "stuccoed" with the fused silica grain, five to eight times. Molds that are thin in section about 3/8" are formed thus accounting for the name "shell" casting.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The "shell" molds were then "fired" during the burnout process and later reheated to 1500 F and molten bronze is poured into the empty cavity, which previously held the wax.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The "shell" molds were then "fired" during the burnout process and later reheated to 1500 F and molten bronze is poured into the empty cavity, which previously held the wax.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The "shell" molds were then "fired" during the burnout process and later reheated to 1500 F and molten bronze is poured into the empty cavity, which previously held the wax.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

At this point, we had twenty-two bronze sections to be cleaned up and assembled by welding the lower sections first and gradually proceeding towards the top. After the arduous task of fabricating the entire sculpture, we still had to do some cosmetic welds. Once the welding "scars" were cosmetically covered up we began the finishing, chasing and sandblasting. Sandblasting magically makes the surface of the bronze clean and uniform making it receptive to tarnish.

Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

Rich Pakkala is welding back together all the separate bronze sections.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

Sean Poston is helping Pakkala with the grinding and assembly.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

A heavy sledge hammer had to be used to correct some distortions occurred during the casting process.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The willow branches that rise up through Gaia's torso were cast in short two feet sections. David Caldwell and I sorted out and assembled and welded all the individual branches.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The final chasing and sanding of the surface texture created an effect of visual unity and harmony.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

After completing all chasing and finishing we proceeded to weld the branches on Gaia's body. The final effect was quite remarkable! The sculpture appeared as if it was cast in one single piece.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

The surface of the sculpture was sand blasted with silica sand and pressure washed to prepare the surface to receive the chemical patina.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard

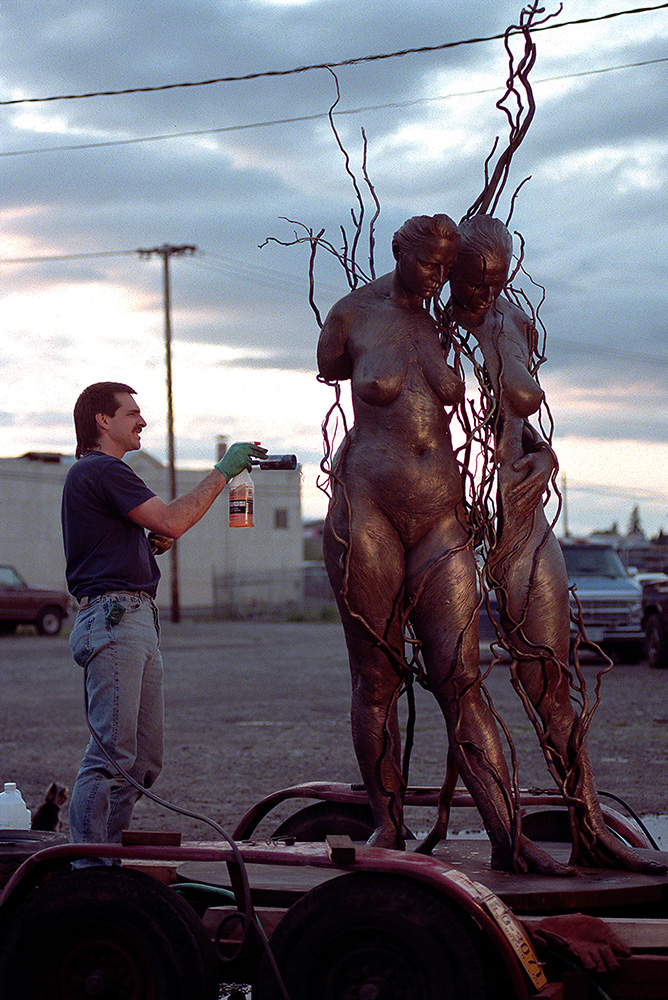

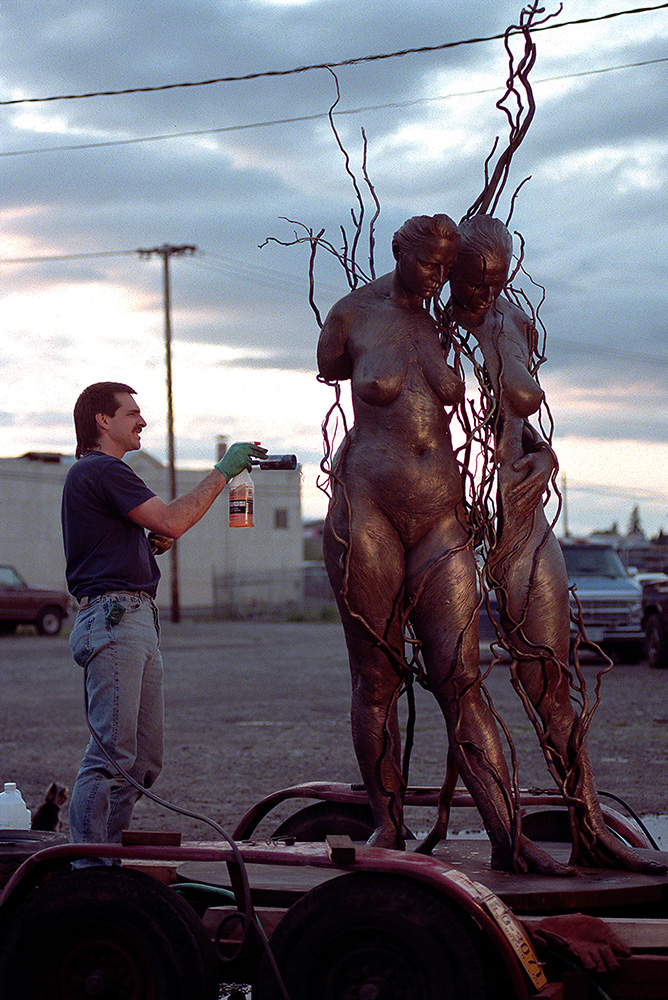

Potassium Sulfate, Ferric Nitrate and Cupric Nitrate were sprayed in layers on the pre- heated surface of the metal, causing an immediate colorful tarnishing of the bronze. A thin layer of paste wax was then applied over the entire surface to seal and protect the metal.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guardc

At last we were able to exhale, step back and enjoy the sight of the finished sculpture.

photo: Nicole DeVito Register-Guard